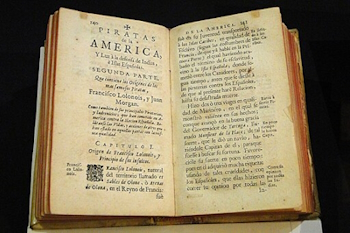

Francois l’Olonnais was renowned for being particularly cruel and was especially feared by the Spanish colonists. Very little is know about his early life. It is known that his real name was Jean-David Nau and that he later became known as Francois l’Olonnais, meaning Frenchman from Sables-d’Olonne, referring the place he was born in sometime between 1630 and 1635. It is thought he received this name while on Tortuga. He was also sometimes simply known as Captain Francois. His family were so poor they sold him or he sold himself as an indentured servant to the French West India Company when he was fifteen. At first, he was sent to work on a sugar plantation in the French colony of Martinique in the Caribbean in the 1650s, sometime later ending up on Tortuga, off the coast of Hispaniola. While serving his three-year indenture, he got to know many buccaneers. What we know of this infamous pirate captain comes mostly from Alexandre Exquemelin’s 1678 account in the Dutch version The History of the Buccaneers of America. It’s not sure if Exquemelin ever met l’Olonnais while on Tortuga from 1666 and 1667 when he too was an indentured servant, possibly gaining his information by talking to other captains and buccaneer crews.

Francois l’Olonnais was renowned for being particularly cruel and was especially feared by the Spanish colonists. Very little is know about his early life. It is known that his real name was Jean-David Nau and that he later became known as Francois l’Olonnais, meaning Frenchman from Sables-d’Olonne, referring the place he was born in sometime between 1630 and 1635. It is thought he received this name while on Tortuga. He was also sometimes simply known as Captain Francois. His family were so poor they sold him or he sold himself as an indentured servant to the French West India Company when he was fifteen. At first, he was sent to work on a sugar plantation in the French colony of Martinique in the Caribbean in the 1650s, sometime later ending up on Tortuga, off the coast of Hispaniola. While serving his three-year indenture, he got to know many buccaneers. What we know of this infamous pirate captain comes mostly from Alexandre Exquemelin’s 1678 account in the Dutch version The History of the Buccaneers of America. It’s not sure if Exquemelin ever met l’Olonnais while on Tortuga from 1666 and 1667 when he too was an indentured servant, possibly gaining his information by talking to other captains and buccaneer crews.

L’Olonnais the pirate

After his indenture was complete l’Olonnais joined the buccaneers of Tortuga and was eventually given a ship to command, operating as a privateer for the French. He was famed for his cruelty towards any Spaniards he captured, becoming known as “Le Fléau des Espagnols” or “The Scourge of the Spanish.” Although exact dates in his pirating career are vague or uncertain, it is known he operated out of Tortuga. Early in his career, he was allegedly shipwrecked near Campeche in Mexico, where he and his men were attacked and almost wiped out by the Spanish. Wounded, l’Olonnais only survived by hiding himself among the bloody corpses of his comrades. He then made his way back to Tortuga in a canoe with the help of some escaped slaves. Later he sailed to Los Cayos on the southern coast of Cuba with a small group of pirates. The Governor was warned by fishermen, but at first he didn’t believe what he was told, as he wrongly thought l’Olonnais had been killed in Campeche. Finally, he sent a 10-gun ship with a crew of ninety to catch the pirates and bring him back alive to Cuba, but l’Olonnais and his men captured the ship while it was at anchor in the mouth of the river Estera. It is said the only survivor was sent back to the governor with a message, the other eighty-seven Spanish crewmen all apparently having been brutally beheaded. The message was as follows: “I shall never henceforward give quarter to any Spaniard whatsoever, and I have great hopes I shall execute on your own person the very same punishment I have done upon them you sent against me. Thus I have retaliated the kindness you designed to me and my companions.”

After his indenture was complete l’Olonnais joined the buccaneers of Tortuga and was eventually given a ship to command, operating as a privateer for the French. He was famed for his cruelty towards any Spaniards he captured, becoming known as “Le Fléau des Espagnols” or “The Scourge of the Spanish.” Although exact dates in his pirating career are vague or uncertain, it is known he operated out of Tortuga. Early in his career, he was allegedly shipwrecked near Campeche in Mexico, where he and his men were attacked and almost wiped out by the Spanish. Wounded, l’Olonnais only survived by hiding himself among the bloody corpses of his comrades. He then made his way back to Tortuga in a canoe with the help of some escaped slaves. Later he sailed to Los Cayos on the southern coast of Cuba with a small group of pirates. The Governor was warned by fishermen, but at first he didn’t believe what he was told, as he wrongly thought l’Olonnais had been killed in Campeche. Finally, he sent a 10-gun ship with a crew of ninety to catch the pirates and bring him back alive to Cuba, but l’Olonnais and his men captured the ship while it was at anchor in the mouth of the river Estera. It is said the only survivor was sent back to the governor with a message, the other eighty-seven Spanish crewmen all apparently having been brutally beheaded. The message was as follows: “I shall never henceforward give quarter to any Spaniard whatsoever, and I have great hopes I shall execute on your own person the very same punishment I have done upon them you sent against me. Thus I have retaliated the kindness you designed to me and my companions.”

The attack on Maracaibo

L’Olonnais’ most famous feat was the capturing and sacking of the Spanish colonial towns of Maracaibo and Gibraltar in modern day Venezuela. In April 1667, his expedition set out from Tortuga with a fleet of eight ships and a crew of 440 pirates, joining forces with the French buccaneer Michel le Basque. It wasn’t the first time Maracaibo had been attacked: The Dutch corsair Henrik de Gerard plundered the city in 1614; British pirate, William Jackson, in 1642. With his fleet increasing to some 700 men on the way, they eventually arrived on the coast of South America in July 1667. On the way, l’Olonnais captured a Spanish treasure ship at Punta Espada near Maracaibo, which was carrying a large cargo of cocoa beans, gemstones, and 260,000 Spanish dollars. This, together with another captured Spanish vessel, was incorporated into his fleet. In August the small armada captured the formidable San Carlos de la Barra Fortress, which guarded the entrance to Lake Maracaibo, from the landward side after landing eighteen miles down the coast.

L’Olonnais’ most famous feat was the capturing and sacking of the Spanish colonial towns of Maracaibo and Gibraltar in modern day Venezuela. In April 1667, his expedition set out from Tortuga with a fleet of eight ships and a crew of 440 pirates, joining forces with the French buccaneer Michel le Basque. It wasn’t the first time Maracaibo had been attacked: The Dutch corsair Henrik de Gerard plundered the city in 1614; British pirate, William Jackson, in 1642. With his fleet increasing to some 700 men on the way, they eventually arrived on the coast of South America in July 1667. On the way, l’Olonnais captured a Spanish treasure ship at Punta Espada near Maracaibo, which was carrying a large cargo of cocoa beans, gemstones, and 260,000 Spanish dollars. This, together with another captured Spanish vessel, was incorporated into his fleet. In August the small armada captured the formidable San Carlos de la Barra Fortress, which guarded the entrance to Lake Maracaibo, from the landward side after landing eighteen miles down the coast.

After thwarting an ambush, the buccaneers captured the city of 4000 inhabitants, but found most residents had fled with their possessions, believing the number of attackers to be much higher. L’Olonnais and his men tracked many of them down and tortured them until they revealed the location of their valuables. It is said l’Olonnais took great pleasure in tormenting captives and was very inventive in his methods. After spending two months in Maracaibo, they moved on to the town of Gibraltar, approaching it by land and seizing it despite the numerical superiority of the Spanish defenders and their native allies. The pirates are thought to have lost some 40 men plus more than 30 wounded, the Spanish far more. Despite receiving a generous ransom of 20,000 pieces of eight and 500 cattle, the pirates sacked and plundered the town for all it was worth, which amounted to 260,000 pieces of eight plus gems and silverware. They also ransomed Maracaibo to obtain yet more money and cattle from the Spanish before leaving. In October 1666, after four weeks, they left Gibraltar and returned to Tortuga to enjoy their ill-gotten gains.

A failed expedition

L’Olonnais mounted another expedition in June 1667. He is thought to have departed Tortuga with 700 pirates with the aim of plundering the towns on Lake Nicaragua as Morgan had done in 1665. They headed for Gracias a Dios in modern day Nicaragua, but were blown off course, ending up in Campeche on the Honduran coast. Running low on provisions, they landed on the coast, terrorizing the local indigenous communities, sowing hatred of the buccaneers which would come back to haunt them later. In September 1667, after capturing the small settlement of Puerto de Caballos and seizing a Spanish ship moored there, they marched inland on the town of San Pedro, which was located thirty miles away through the jungle. After overcoming a Spanish ambush, they drove their foes before them, torturing and killing captives to find out the positions of the Spanish soldiers, whom the buccaneers feared would encircle them. They eventually took San Pedro with heavy losses, but found most inhabitants had already fled with their valuables. After burning the town l’Olonnais headed back to the coast with his men. On receiving information that a richly laden Spanish ship would arrive in Puerto de Caballos within a couple of months, the pirates decided to wait for its arrival. When it finally arrived and was captured in November 1667, they were disappointed to discover it was only carrying paper and steel. According to Exquemelin, some buccaneers left in disappointment, returning to Tortuga or sailing the Caribbean in search of more prizes, which might or might not be true. Either all or some of the buccaneers next sailed to Belize to repair their ship. They established themselves on a small island call Abraham’s Kay, where they nurtured friendly relations with the local Tipu Mayans. The natives wanted the buccaneers to aid them against their enemies, but the ever mistrustful l’Olonnais declined.

L’Olonnais’ fate

Exquemelin’s account of l’Olonnais’ end is the only one to exist and comes from the alleged sole survivor of the Indian attack that cost l’Olonnais his life. It is possible this witness never existed and was only invented by Exquemelin to make his story more interesting. What we do know is that l’Olonnais disappeared sometime in 1668. He is said to have met Henry Morgan while anchored off Gracias a Dios, when half his company joined Morgan or returned to Tortuga. L’Olonnais is then thought to have returned to the San Pedro area with about 300 men, using it as a base from which to launch raids, but his ship ran aground on a sandbar near the islands of De Las Puertas in the Gulf of Honduras. While trying to free their vessel, l’Olonnais came under constant attack from the natives, who were out for revenge. The buccaneer’s numbers gradually dwindling, his men built barges out of the stranded ship in an attempt to escape. After several months they had completed the construction of their boat and acquired seven canoes, although not enough to carry all of them. L’Olonnais left with 112 of his men, promising to return for the others in a proper ship.

Exquemelin’s account of l’Olonnais’ end is the only one to exist and comes from the alleged sole survivor of the Indian attack that cost l’Olonnais his life. It is possible this witness never existed and was only invented by Exquemelin to make his story more interesting. What we do know is that l’Olonnais disappeared sometime in 1668. He is said to have met Henry Morgan while anchored off Gracias a Dios, when half his company joined Morgan or returned to Tortuga. L’Olonnais is then thought to have returned to the San Pedro area with about 300 men, using it as a base from which to launch raids, but his ship ran aground on a sandbar near the islands of De Las Puertas in the Gulf of Honduras. While trying to free their vessel, l’Olonnais came under constant attack from the natives, who were out for revenge. The buccaneer’s numbers gradually dwindling, his men built barges out of the stranded ship in an attempt to escape. After several months they had completed the construction of their boat and acquired seven canoes, although not enough to carry all of them. L’Olonnais left with 112 of his men, promising to return for the others in a proper ship.

They then sailed south to Nicaragua, but on landing were ambushed by the Spanish, who killed twenty-eight of the buccaneers and captured four. The rest fled into the jungle, and it is at this point that l’Olonnais disappears from historical record. Exquemelin, the sole source for what then happened to the pirate captain, says the buccaneers came under attack from local Kuna tribe as they tried to get to Cartagena in Colombia, desperate for food. They were captured by the natives of Darién, a modern-day province of Panama, and were eventually wiped out, except for the one survivor, who remained under the Kuna, later to report on the fate of l’Olonnais, saying: “The locals tore him in pieces, throwing his body limb by limb into the fire, and his ashes into the air, that no trace or memory might remain of such an infamous, inhuman creature.” The brutish pirate met, what some might say, a well-deserved brutal end, if it indeed did happen that way. In fact, it is difficult to determine how much of the cruel reputation attributed to l’Olonnais was fact and how much propaganda or for dramatic effect.

If your interested in finding out more about François l’Olonnais, watched the detailed video by Gold and Gunpowder.