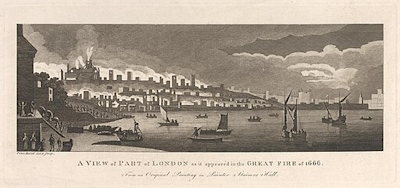

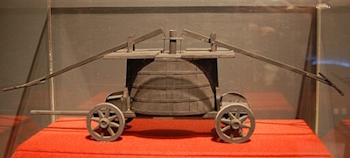

By the time the Great Fire occurred, London was by far the largest city in England. Its inhabitants numbering between 300,000 and 400,000, it had become a crowded, unregulated sprawl of houses. This wasn’t the first large scale fire, the city having experienced several major fires in the past, the most recent having been in 1633. Additionally, London had been hit by an epidemic of bubonic plague called the Great Plague of London only the year before, during which between 60,000 and 100,000 are thought to have died. As well as disease, fires were always a danger in a city made mostly of timber and tar paper. There were so many possible causes: fireplaces, candles, ovens, lamps, as well a large stores of combustibles such as pitch and hemp. To combat the perpetual danger, there were watchmen, also known as bellmen, who patrolled the city at night, who sounded the alarm should a fire break out. Once discovered, there was no modern fire brigade to deal with the fire. Some rudimentary ‘fire engines’ were available at the time, although they were generally cumbersome and ineffective. Extinguishing fires was a community effort using a combination of demolition and water, and by law every parish needed to have a store of fire fighting equipment such as ladders, buckets, and firehooks for pulling down buildings. Considering the extent of the fire, it is surprising that, the death toll was relatively small, although the damage to property was extensive.

By the time the Great Fire occurred, London was by far the largest city in England. Its inhabitants numbering between 300,000 and 400,000, it had become a crowded, unregulated sprawl of houses. This wasn’t the first large scale fire, the city having experienced several major fires in the past, the most recent having been in 1633. Additionally, London had been hit by an epidemic of bubonic plague called the Great Plague of London only the year before, during which between 60,000 and 100,000 are thought to have died. As well as disease, fires were always a danger in a city made mostly of timber and tar paper. There were so many possible causes: fireplaces, candles, ovens, lamps, as well a large stores of combustibles such as pitch and hemp. To combat the perpetual danger, there were watchmen, also known as bellmen, who patrolled the city at night, who sounded the alarm should a fire break out. Once discovered, there was no modern fire brigade to deal with the fire. Some rudimentary ‘fire engines’ were available at the time, although they were generally cumbersome and ineffective. Extinguishing fires was a community effort using a combination of demolition and water, and by law every parish needed to have a store of fire fighting equipment such as ladders, buckets, and firehooks for pulling down buildings. Considering the extent of the fire, it is surprising that, the death toll was relatively small, although the damage to property was extensive.

Who or what started the fire?

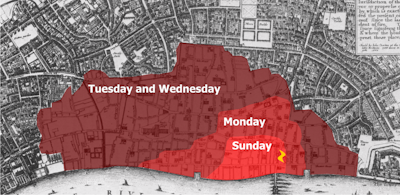

The fire started at 1 am on Sunday 2nd December 1666 in a bakery in Pudding Lane, which was located not far from London Bridge and the Thames. It had been one of the warmest summers in a long time with a lack of rainfall in the south-east of England and river levels running low. The fire itself was most likely caused by a stray ember from one of the five ovens the bakery is reported as having, which ignited a pile of twigs. The baker, Thomas Farynor, who lived with his family above the bakery, claimed the fire had been started by arson and is reported as saying that he had carefully checked all the rooms before going to bed. The baker’s son, Thomas, was the first to notice it. He alerted the rest of the family, who escaped through an upstairs windows and climbed onto the roof of a neighbouring house. The maid was too afraid to jump and perished in the flames, becoming the first victim.

The fire started at 1 am on Sunday 2nd December 1666 in a bakery in Pudding Lane, which was located not far from London Bridge and the Thames. It had been one of the warmest summers in a long time with a lack of rainfall in the south-east of England and river levels running low. The fire itself was most likely caused by a stray ember from one of the five ovens the bakery is reported as having, which ignited a pile of twigs. The baker, Thomas Farynor, who lived with his family above the bakery, claimed the fire had been started by arson and is reported as saying that he had carefully checked all the rooms before going to bed. The baker’s son, Thomas, was the first to notice it. He alerted the rest of the family, who escaped through an upstairs windows and climbed onto the roof of a neighbouring house. The maid was too afraid to jump and perished in the flames, becoming the first victim.

Rumours about who started the blaze spread as fast as the fire itself. Among those accused were foreigners, Catholics, and the homeless. Fears mainly focused on the Dutch, England’s enemies in the ongoing Second Anglo-Dutch War, and their allies the French. These substantial immigrant groups became victims of street violence and had to be protected by soldiers, although there are some reports that some of those troops joined in the violence instead of preventing it. Not all placed the blame on England’s enemies, some claiming it was God’s wrath and even that the End of Days had arrived. This theory was especially popular among the puritans who criticised the decadent ways of Charles II and his court. The renowned astrologer William Lilly was even suspected at one point, because of a pamphlet he had published in 1651 called Monarch or no Monarchy, in which a burning city was depicted. He was later released after a mentally disturbed French watchmaker named Robert Hubert, who believed he was a French spy, confessed to starting the fire. Although his story made little sense and he wasn’t believe by most, he was hanged on 29th October 1666 anyway as a convenient scapegoat.

The fire spreads

One of the bakery’s neighbours claimed the fire took an hour or so to spread to nearby buildings. Houses were built very close together in those days with streets tending to be narrower at the top than at the bottom due to projections called jetties, which were so close to each other that they were almost touching. Charles II had tried to ban this practice in 1661, but it was mostly ignored, even though builders faced a possible jail sentence if they didn’t comply. Additionally, houses were made of combustible materials such as wattle, panels of woven wood, filled with daub, which was a mixture of mud and dung. If well-maintained this might have prevented a rapid spread of the fire, but as walls were generally in poor condition, especially in poorer areas, the exposed wood burnt readily.

One of the bakery’s neighbours claimed the fire took an hour or so to spread to nearby buildings. Houses were built very close together in those days with streets tending to be narrower at the top than at the bottom due to projections called jetties, which were so close to each other that they were almost touching. Charles II had tried to ban this practice in 1661, but it was mostly ignored, even though builders faced a possible jail sentence if they didn’t comply. Additionally, houses were made of combustible materials such as wattle, panels of woven wood, filled with daub, which was a mixture of mud and dung. If well-maintained this might have prevented a rapid spread of the fire, but as walls were generally in poor condition, especially in poorer areas, the exposed wood burnt readily.

The rapid spread could have been prevented by knocking down any structures in the path of a fire to stop it extending its reach. Unfortunately for the city, the decision to do this was delayed by the Lord Mayor, Sir Thomas Bloodworth, who was reluctant to tear down the houses of wealthy merchants to create a firebreak. Furthermore, offers from Charles II to send troops, the Royal Life Guards, to help combat the flames were initially rejected by mistrustful city officials, many of whom had fought on the side of parliament in the English Civil War. The fire was exacerbated by the long, hot dry summer, so by Sunday Morning it had burned down an estimated 300 houses as it expanded towards the riverfront, even setting the houses on London Bridge ablaze. By Sunday afternoon the fire had become a raging inferno with a tremendous uprush of hot air above the flames. On the first day very few people took the fire as seriously as they should have and paid little thought to leaving the city, instead moving themselves and their belongings to what they deemed safer areas within the city. By Sunday evening it had travelled 1200 feet (500 metres) along the riverbank.

The fire rages on

On Monday, the fire was pushed towards the heart of the city by the wind, which also served to increase the temperature of the fire. When people really started to realise the seriousness of the situation, panic started. As it was spreading to the west and north towards the wealthier areas, the King’s brother, the future James II, took control of the situation and attempted to re-established some kind of order by concentrating efforts of fighting the fire. The spread south was mainly checked by the river, although the buildings on London Bridge were set ablaze. The spread to the south of the river via the bridge was prevented by an open space set up between it and the nearby buildings. By Monday evening it had become clear that the old walls of the city wouldn’t prevent the flames from spreading and by Tuesday the blaze had spread to most of the city, springing over the river Fleet, which had failed to act as a barrier to the spread. St Paul’s Cathedral was engulfed in flames, the blaze aided by the wooden scaffolding erected to carry out repairs and the mass of goods stashed there by people who believed the robust, stone building to be a safe haven for their possessions. The fire almost reached the Tower of London, but was prevented from doing so when the garrison demolished nearby buildings as a firebreak. Fortunately, the wind dropped by Tuesday evening, making it easier to combat the flames.

Putting the fire out

Attempts to build chains of people passing buckets of water from pipes and pumps to put out the flames had largely failed because of the widespread panic. Firefighting efforts were impeded by the narrowness of the streets in addition to the mass of fleeing refugees. The high Roman wall enclosing the city impeded escape from the flames, egress being restricted to eight narrow gates. The gates were even shut for a while to deter people from concentrating their energies on saving their possessions and instead to turning their attentions to fighting the fire. In many places it was difficult to get close to the fire due to the intense heat, which didn’t start to die down until Wednesday morning. There were two key factors that led to the extinguishing of the fire: the subsiding of the strong east wind; the Tower of London garrison using gunpowder to create effective firebreaks, halting further spread eastward. The fire is said to have died out in Smithfield where the Golden Boy of Pye Corner monument now stands, although there were still numerous isolated fires burning throughout the city. In some places embers are reported to have been still glowing a month afterwards.

Attempts to build chains of people passing buckets of water from pipes and pumps to put out the flames had largely failed because of the widespread panic. Firefighting efforts were impeded by the narrowness of the streets in addition to the mass of fleeing refugees. The high Roman wall enclosing the city impeded escape from the flames, egress being restricted to eight narrow gates. The gates were even shut for a while to deter people from concentrating their energies on saving their possessions and instead to turning their attentions to fighting the fire. In many places it was difficult to get close to the fire due to the intense heat, which didn’t start to die down until Wednesday morning. There were two key factors that led to the extinguishing of the fire: the subsiding of the strong east wind; the Tower of London garrison using gunpowder to create effective firebreaks, halting further spread eastward. The fire is said to have died out in Smithfield where the Golden Boy of Pye Corner monument now stands, although there were still numerous isolated fires burning throughout the city. In some places embers are reported to have been still glowing a month afterwards.

The devastation

As much as 85% of the city was destroyed in the fire. It is thought that about 13,500 houses and other buildings were burnt down, as well as 86 churches being gutted. St. Paul’s Cathedral, the Royal Exchange, and London Bridge were all badly damaged. Financial losses, including the loss of trade, was extremely high, amounting to over two billion pounds in today’s money. Additionally, up to 200,000 homeless refugees had fled the flames, many camping out in parks such as Moorfield, which lay to the north of the city. Flight from London and settlement elsewhere were strongly encouraged by Charles II, who feared a London rebellion amongst the dispossessed refugees. He ordered that bread be delivered daily to alleviate the suffering and placate the displaced population. Surprisingly, despite the extent of the devastation, only six to eight deaths have been attributed directly to the fire, although many others might have gone unrecorded. In addition to those deaths, many more people probably died of hunger and disease in the following weeks. Not only human the inhabitants of the city fell victim to the flames. For example, thousands of pigeons that the Londoners kept for food burnt to death, being reluctant to leave their homes, instead hovering over their residence until their wings were burnt and they plummeted into the flames. As with all disasters, there were those who took advantage of the chaos, either looting, absconding with the items they were paid to carry away from the flames, or charging exorbitant prices, such as for the rental of a cart, which had cost a couple of shillings before the fire, but had risen to £40 by Monday.

As much as 85% of the city was destroyed in the fire. It is thought that about 13,500 houses and other buildings were burnt down, as well as 86 churches being gutted. St. Paul’s Cathedral, the Royal Exchange, and London Bridge were all badly damaged. Financial losses, including the loss of trade, was extremely high, amounting to over two billion pounds in today’s money. Additionally, up to 200,000 homeless refugees had fled the flames, many camping out in parks such as Moorfield, which lay to the north of the city. Flight from London and settlement elsewhere were strongly encouraged by Charles II, who feared a London rebellion amongst the dispossessed refugees. He ordered that bread be delivered daily to alleviate the suffering and placate the displaced population. Surprisingly, despite the extent of the devastation, only six to eight deaths have been attributed directly to the fire, although many others might have gone unrecorded. In addition to those deaths, many more people probably died of hunger and disease in the following weeks. Not only human the inhabitants of the city fell victim to the flames. For example, thousands of pigeons that the Londoners kept for food burnt to death, being reluctant to leave their homes, instead hovering over their residence until their wings were burnt and they plummeted into the flames. As with all disasters, there were those who took advantage of the chaos, either looting, absconding with the items they were paid to carry away from the flames, or charging exorbitant prices, such as for the rental of a cart, which had cost a couple of shillings before the fire, but had risen to £40 by Monday.

The aftermath

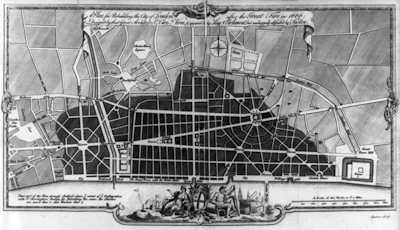

Trauma to the inhabitants of London caused by the fire and a fear of an invasion resulted in refugees lynching any foreigners who were unlucky enough to come their way. This happened not only in London, but across the country, despite the official account of the fire in the London Gazette concluding that it had been an accident, an act of God. The social and economic problems created by the disaster were overwhelming. Various schemes for rebuilding the city were proposed, some of them very radical, but most importantly, brick was used extensively in the rebuilding. Furthermore, the Rebuilding of London Act 1666 banned wood from the exterior of buildings. A newly designed St. Paul’s Cathdral was rebuilt under the supervision of Sir Christopher Wren and still stands today. London was reconstructed on essentially the same medieval street plan, which still exists today. Thomas Farynor rebuilt his bakery in Pudding land and died 4 years later.

Trauma to the inhabitants of London caused by the fire and a fear of an invasion resulted in refugees lynching any foreigners who were unlucky enough to come their way. This happened not only in London, but across the country, despite the official account of the fire in the London Gazette concluding that it had been an accident, an act of God. The social and economic problems created by the disaster were overwhelming. Various schemes for rebuilding the city were proposed, some of them very radical, but most importantly, brick was used extensively in the rebuilding. Furthermore, the Rebuilding of London Act 1666 banned wood from the exterior of buildings. A newly designed St. Paul’s Cathdral was rebuilt under the supervision of Sir Christopher Wren and still stands today. London was reconstructed on essentially the same medieval street plan, which still exists today. Thomas Farynor rebuilt his bakery in Pudding land and died 4 years later.

For more information on the Great Fire of London watch the video below by MedievalMadness.