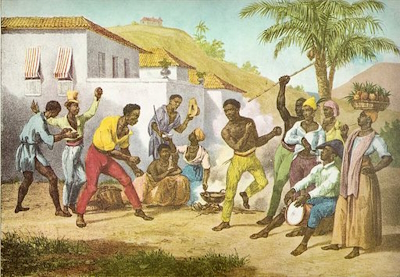

In the early 17th century an autonomous, self-sufficient community of escaped slaves (maroons) known as Palmares established itself in the Captaincy of Pernambuco in north-eastern Brazil. It grew considerably throughout the 17th century, eventually becoming the largest settlement ever founded by runaway slaves in Brazil. Most of the information about this community comes from Portuguese and Dutch colonists and many of the names of those involved are unknown. At its apex, the population of Palmares reached somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000. The Palmaristas constantly resisted Portuguese and Dutch attacks while at the same time carrying out their own raids on the colonists. In the 1500s nearly half of all those enslaved from Africa were transported to Brazil, which was governed by the Portuguese at the time. Their settlements, called mocambos or quilombos, were constructed in the land’s interior, although the later is a modern term. At its height in the 1660s, Quilombo of Palmares was a confederation with a central capital and associated fortified towns and villages. It had its own military and an elected leader or king – Ganga Zumba. Their society was based on African sociopolitical models merging with European influences. Churches were common in the settlements of Palmares as many Angolan slaves had been baptized even before their capture, although African religious practices were also thought to have been preserved. The population was swelled by indigenous people; caboclos, who were a result of the pairing of the indigenous population with European settlers, as well as and some poor, white settlers together with soldiers who had deserted. The Palmaristas often traded their agricultural products with Portuguese colonists for gunpowder and salt, as resources were scare in colonies, forcing the colonists to find a balance between enmity and trade. In the 17th Century, the Portuguese authorities constantly had to juggle many threats to their power, of which Palmares was only one. Others included Dutch invaders, indigenous uprisings, and the mass escape of slaves.

In the early 17th century an autonomous, self-sufficient community of escaped slaves (maroons) known as Palmares established itself in the Captaincy of Pernambuco in north-eastern Brazil. It grew considerably throughout the 17th century, eventually becoming the largest settlement ever founded by runaway slaves in Brazil. Most of the information about this community comes from Portuguese and Dutch colonists and many of the names of those involved are unknown. At its apex, the population of Palmares reached somewhere between 10,000 and 20,000. The Palmaristas constantly resisted Portuguese and Dutch attacks while at the same time carrying out their own raids on the colonists. In the 1500s nearly half of all those enslaved from Africa were transported to Brazil, which was governed by the Portuguese at the time. Their settlements, called mocambos or quilombos, were constructed in the land’s interior, although the later is a modern term. At its height in the 1660s, Quilombo of Palmares was a confederation with a central capital and associated fortified towns and villages. It had its own military and an elected leader or king – Ganga Zumba. Their society was based on African sociopolitical models merging with European influences. Churches were common in the settlements of Palmares as many Angolan slaves had been baptized even before their capture, although African religious practices were also thought to have been preserved. The population was swelled by indigenous people; caboclos, who were a result of the pairing of the indigenous population with European settlers, as well as and some poor, white settlers together with soldiers who had deserted. The Palmaristas often traded their agricultural products with Portuguese colonists for gunpowder and salt, as resources were scare in colonies, forcing the colonists to find a balance between enmity and trade. In the 17th Century, the Portuguese authorities constantly had to juggle many threats to their power, of which Palmares was only one. Others included Dutch invaders, indigenous uprisings, and the mass escape of slaves.

Continuous warfare

In 1630, the Dutch sent a fleet to conquer Pernambuco during the lengthy Dutch-Portuguese War of 1598-1663. The Dutch quickly captured and held the city of Recife, but were unable or unwilling to conquer the rest of the province. The residents of Palmares used the conflict to strengthen their position. As a result of the constant low-intensity war between Dutch and Portuguese settlers, thousands of enslaved Africans escaped and fled to the Palmares. The Dutch leader John Maurice of Nassau sent several expeditions against Palmares before the Dutch were eventually driven out by the Portuguese in 1654. An outpost was built in Serinhaém by the Portuguese in 1672 who carried out direct attacks against Palmares, even offering an amnesty to prisoners who took part in these expeditions. Bushland relatively close to Palmares was destroyed and several settlements were besieged, in an attempt to starve out the people of Palmares. Despite many setbacks, the Palmaristas were able to fend off these constant attacks. After a particularly devastating attack by the captain Fernão Carrilho in 1676–77, which resulted in the capture of some of his relatives, Ganga Zumba sent a letter to the Governor of Pernambuco asking for peace.

In 1630, the Dutch sent a fleet to conquer Pernambuco during the lengthy Dutch-Portuguese War of 1598-1663. The Dutch quickly captured and held the city of Recife, but were unable or unwilling to conquer the rest of the province. The residents of Palmares used the conflict to strengthen their position. As a result of the constant low-intensity war between Dutch and Portuguese settlers, thousands of enslaved Africans escaped and fled to the Palmares. The Dutch leader John Maurice of Nassau sent several expeditions against Palmares before the Dutch were eventually driven out by the Portuguese in 1654. An outpost was built in Serinhaém by the Portuguese in 1672 who carried out direct attacks against Palmares, even offering an amnesty to prisoners who took part in these expeditions. Bushland relatively close to Palmares was destroyed and several settlements were besieged, in an attempt to starve out the people of Palmares. Despite many setbacks, the Palmaristas were able to fend off these constant attacks. After a particularly devastating attack by the captain Fernão Carrilho in 1676–77, which resulted in the capture of some of his relatives, Ganga Zumba sent a letter to the Governor of Pernambuco asking for peace.

Unsuccessful in their attacks, the Portuguese agreed to negotiate a peace treaty in 1678. Portugal was drowning in debt because of its conflict with Spain, which lasted until 1668, and various colonial conflicts, returning the Portuguese kingdom to its previous position of ‘the pauper of Europe’. Brazil was practically the only source of income for the Portuguese Crown at the time, so partially because of economic reasons, and partially due to the benefits of trade between the colonists and the Palmaristas, a peace treaty was signed. The independence of Palmares was recognised, as was the freedom of anyone born there, but the ex-slaves would have to pledge loyalty to the crown of Portugal and relocate to the Cucaú Valley. The most bitter term of the agreement was that they were to return any escaped slaves to their Portuguese owners. Many inhabitants of Palmares, led by Ganga Zumba, migrated to the region of Cucaú as part of the agreement. Not all agreed with Ganga Zumba’s decision, and many stayed on to fight under Ganga Zumba’s general and nephew Zumbi, refusing to accept the terms the Portuguese had laid on them. Zumbi was born a free-man in Palmares in 1655, but was captured as a child and raised by a missionary called Father António Melo, who had his ward baptised and educated. Zumbi escaped in 1670 at age of 15, returning to Palmares where he became a respected military strategist. Ganga Zumba was later killed, believed to have been poisoned, possibly by Zumbi’s people, and those of Ganga Zumba’s supporters who didn’t manage to flee were re-enslaved by the Portuguese. Six Portuguese expeditions tried to conquer Palmares between 1680 and 1686, but all failed. The Palmaristas fought an effective guerilla war with ambushes, night raids, and traps playing a central role in their strategy. War raged more or less constantly until 1694.

Unsuccessful in their attacks, the Portuguese agreed to negotiate a peace treaty in 1678. Portugal was drowning in debt because of its conflict with Spain, which lasted until 1668, and various colonial conflicts, returning the Portuguese kingdom to its previous position of ‘the pauper of Europe’. Brazil was practically the only source of income for the Portuguese Crown at the time, so partially because of economic reasons, and partially due to the benefits of trade between the colonists and the Palmaristas, a peace treaty was signed. The independence of Palmares was recognised, as was the freedom of anyone born there, but the ex-slaves would have to pledge loyalty to the crown of Portugal and relocate to the Cucaú Valley. The most bitter term of the agreement was that they were to return any escaped slaves to their Portuguese owners. Many inhabitants of Palmares, led by Ganga Zumba, migrated to the region of Cucaú as part of the agreement. Not all agreed with Ganga Zumba’s decision, and many stayed on to fight under Ganga Zumba’s general and nephew Zumbi, refusing to accept the terms the Portuguese had laid on them. Zumbi was born a free-man in Palmares in 1655, but was captured as a child and raised by a missionary called Father António Melo, who had his ward baptised and educated. Zumbi escaped in 1670 at age of 15, returning to Palmares where he became a respected military strategist. Ganga Zumba was later killed, believed to have been poisoned, possibly by Zumbi’s people, and those of Ganga Zumba’s supporters who didn’t manage to flee were re-enslaved by the Portuguese. Six Portuguese expeditions tried to conquer Palmares between 1680 and 1686, but all failed. The Palmaristas fought an effective guerilla war with ambushes, night raids, and traps playing a central role in their strategy. War raged more or less constantly until 1694.

The fall of Palmares

An army of over a thousand men made up of some local forces, but mainly indigenous allies was organised under the leadership of Domingos Jorge Velho and Bernardo Vieira de Melo. Despite the formidable defences, including redoubts and spike traps, the capital, Cerca do Macaco, was finally captured in 1694, finally putting an end to the republic of ex-slaves. At first believed to be dead, Zumbi managed to escape and attempted to rally his forces, but he was later captured after his hiding place was revealed by a captured warrior, who had been tortured to obtain this information. Zumbi was killed and mutilated by the Portuguese on November 20th 1695. His body was preserved and displayed as a warning to slaves. The victors were rewarded with land that had been part of the Quilombo of Palmares. This didn’t destroy the spirit of Palmares but it did deal a crushing blow. After that, only a few isolated settlements continued the resistance. Although depleted in numbers, the rebels fought on under new leaders until the 1760s.

An army of over a thousand men made up of some local forces, but mainly indigenous allies was organised under the leadership of Domingos Jorge Velho and Bernardo Vieira de Melo. Despite the formidable defences, including redoubts and spike traps, the capital, Cerca do Macaco, was finally captured in 1694, finally putting an end to the republic of ex-slaves. At first believed to be dead, Zumbi managed to escape and attempted to rally his forces, but he was later captured after his hiding place was revealed by a captured warrior, who had been tortured to obtain this information. Zumbi was killed and mutilated by the Portuguese on November 20th 1695. His body was preserved and displayed as a warning to slaves. The victors were rewarded with land that had been part of the Quilombo of Palmares. This didn’t destroy the spirit of Palmares but it did deal a crushing blow. After that, only a few isolated settlements continued the resistance. Although depleted in numbers, the rebels fought on under new leaders until the 1760s.

The legacy of Palmares

Although defeated, the very idea of Palmares would continue to represent the greatest threat of Black resistance in the minds of the colonial authorities. It was essential for them to prevent the emergence of a new Palmares, but as long as slavery persisted, there would continue to be resistance, not only in Brazil but in all of the Americas. It was in itself astounding that such a rebel kingdom of ex-slaves lasted almost a century. Since 1978, the date of Zumbi’s death has been celebrated across Brazil on 20th November, being instituted as the Brazilian National Day of Black Consciousness. Palmares is viewed by many as the start of the struggle for the freedom for blacks in Brazil. Palmares did not end with the death of Zumbi, but survived in the minds of the colonial elites and the enslaved black population as a constant reminder of what was possible. The spectre of further uprisings, like that of Palmares, throughout Brazil would continue to haunt the colonial powers, leading to repressive policies until slavery was finally abolished in Brazil, which was the last country in the Americas to abolish the cruel trade, on 13 May 1888.

Although defeated, the very idea of Palmares would continue to represent the greatest threat of Black resistance in the minds of the colonial authorities. It was essential for them to prevent the emergence of a new Palmares, but as long as slavery persisted, there would continue to be resistance, not only in Brazil but in all of the Americas. It was in itself astounding that such a rebel kingdom of ex-slaves lasted almost a century. Since 1978, the date of Zumbi’s death has been celebrated across Brazil on 20th November, being instituted as the Brazilian National Day of Black Consciousness. Palmares is viewed by many as the start of the struggle for the freedom for blacks in Brazil. Palmares did not end with the death of Zumbi, but survived in the minds of the colonial elites and the enslaved black population as a constant reminder of what was possible. The spectre of further uprisings, like that of Palmares, throughout Brazil would continue to haunt the colonial powers, leading to repressive policies until slavery was finally abolished in Brazil, which was the last country in the Americas to abolish the cruel trade, on 13 May 1888.

For a more detailed analysis of Palmares read the article The Invincible Spirit of Palmares: The Story of Brazil’s Largest Community of Escaped Slaves on the Left Voice website.