Pirates are often viewed a being lawless bunch in need of a strong, authoritative captain figure to keep them in line, but, in fact, they operated under their own strict set of rules, which were often deemed sacred to them. This set rules, commonly known as the Articles of Agreement or the Pirate Code determined everything on board a pirate vessel from the distribution of booty to the allotting of punishments. Overall, pirates were fairly democratic, but the punishments for breaking the agreed upon articles could often be severe. Articles that applied to all were a necessary measure to maintain the cohesion of the crew, many of whom had previously been subjected to the dictatorial methods of merchant and naval captains, so it was important that the crew agreed on what the Articles should cover together with the captain. In contrast, privateer vessels usually had their own charters, assigning larger shares to the officers and owners of the ship and what was left to the rest of the crew, although they sometimes contained points similar to those in the Pirate Code. There wasn’t a single written code for all pirates, each crew deciding on their own articles and what was important to them. Everyone who joined the crew had to sign them, or if illiterate made their mark, swearing an oath to abide by the rules contained therein on a bible or some other object such as a pistol or an axe. The completed Articles were then posted where everyone could then see them.

Pirates are often viewed a being lawless bunch in need of a strong, authoritative captain figure to keep them in line, but, in fact, they operated under their own strict set of rules, which were often deemed sacred to them. This set rules, commonly known as the Articles of Agreement or the Pirate Code determined everything on board a pirate vessel from the distribution of booty to the allotting of punishments. Overall, pirates were fairly democratic, but the punishments for breaking the agreed upon articles could often be severe. Articles that applied to all were a necessary measure to maintain the cohesion of the crew, many of whom had previously been subjected to the dictatorial methods of merchant and naval captains, so it was important that the crew agreed on what the Articles should cover together with the captain. In contrast, privateer vessels usually had their own charters, assigning larger shares to the officers and owners of the ship and what was left to the rest of the crew, although they sometimes contained points similar to those in the Pirate Code. There wasn’t a single written code for all pirates, each crew deciding on their own articles and what was important to them. Everyone who joined the crew had to sign them, or if illiterate made their mark, swearing an oath to abide by the rules contained therein on a bible or some other object such as a pistol or an axe. The completed Articles were then posted where everyone could then see them.

The pirates of the Golden Age adapted their articles from what was know as the Coutume de la Coste, or Custom of the Coast, based on those put together by buccaneers know as the Brethren of the coast in about 1640. The Custom of the Coast of the buccaneers was never written down and was considered to be flexible, tribunals often being held on land to sort out disputes. It later developed into what was known as the Chasse-Partie, Charter Party, Articles of Agreement, or Jamaica Discipline, in which it was stated that the captain’s power had to be counterbalanced by that of an elected quartermaster, who had the crew’s best interests at heart. It also determined that any plunder was to be strictly divided into shares. Each ship wrote down its own version of these articles, but they all shared some common themes such as how to divide the plunder. Some seamen were forced into piracy, especially much sought after surgeons and carpenters, who often refused or were pressured to sign the articles, such as Thomas South and Thomas Davis, who were two carpenters captured by Sam Bellamy. Not signing meant not getting a share of the loot and being treated as little more than a slave. Those who refused to sign hoped by not profiting from the ill-gotten gains, they would be treated more leniently should they be captured. Some were allowed to refuse, but others coerced into signing on pain of mistreatment, like the pressed pirate William Phillips, who after being taken by Captain John Phillips, later gave in and signed to escape harsh treatment or death.

What was dealt with in the pirate articles?

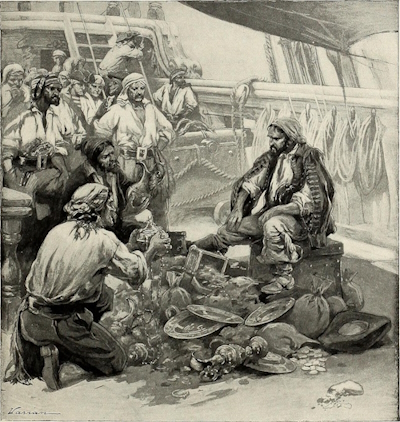

There were several themes common to most pirate articles implemented in the attempt to maintain order on the vessel. One was the banning of gambling on board to prevent disputes. For a similar reason women were generally not allowed on board, although some believe it was because the presence of women on a ship brought bad fortune. Physical disputes, which might have disrupted the daily running of the ship, were to be sorted out on shore. The restriction on the consumption of alcohol on some ships was to likewise prevent disturbances. Smoking and the use of naked flames were also restricted, because of the obvious danger to a vessel made entirely of combustible material and the presence of gun powder – fire was a constant hazard aboard ships of the time. The fair distribution of loot was important to maintain harmony, and appropriating any plunder and hiding it was a punishable offence. A compensation scheme for injuries also helped foster motivation and lend the feeling of security to the pirate crew. Pensions and compensation for injury were not new at the time, as, for example, the French navy already paid pensions to retired and invalid sailors. In England, the Chatham Chest, an early pension scheme into which sailors paid contributions, was set up in 1590 to ensure crippled sailors received money to support themselves. As well as benefits, punishments were a common theme mentioned in the Articles with various measures decided on by the captain and crew, ranging from whipping to marooning, and even death. There is no evidence that walking the plank was ever used, although plenty of victims were thrown into the sea. Another important topic regulated in the Articles was combat. Weapons needed to be kept ready for use and there needed to be a clear command structure when engaging another vessel to avoid chaos and defeat. It was generally only during combat that the captain had absolute control over the ship. Whatever the rules in the Articles, they were usually there for the safety of all on board and to avert unnecessary conflicts.

There were several themes common to most pirate articles implemented in the attempt to maintain order on the vessel. One was the banning of gambling on board to prevent disputes. For a similar reason women were generally not allowed on board, although some believe it was because the presence of women on a ship brought bad fortune. Physical disputes, which might have disrupted the daily running of the ship, were to be sorted out on shore. The restriction on the consumption of alcohol on some ships was to likewise prevent disturbances. Smoking and the use of naked flames were also restricted, because of the obvious danger to a vessel made entirely of combustible material and the presence of gun powder – fire was a constant hazard aboard ships of the time. The fair distribution of loot was important to maintain harmony, and appropriating any plunder and hiding it was a punishable offence. A compensation scheme for injuries also helped foster motivation and lend the feeling of security to the pirate crew. Pensions and compensation for injury were not new at the time, as, for example, the French navy already paid pensions to retired and invalid sailors. In England, the Chatham Chest, an early pension scheme into which sailors paid contributions, was set up in 1590 to ensure crippled sailors received money to support themselves. As well as benefits, punishments were a common theme mentioned in the Articles with various measures decided on by the captain and crew, ranging from whipping to marooning, and even death. There is no evidence that walking the plank was ever used, although plenty of victims were thrown into the sea. Another important topic regulated in the Articles was combat. Weapons needed to be kept ready for use and there needed to be a clear command structure when engaging another vessel to avoid chaos and defeat. It was generally only during combat that the captain had absolute control over the ship. Whatever the rules in the Articles, they were usually there for the safety of all on board and to avert unnecessary conflicts.

Democracy on pirate ships

Although by no means perfect, the Pirate Code helped maintain an air of equality on a pirate ship in the Golden Age, at a time in which absolutist monarchies, such as Louis XIV of France, or restricted democracies, in which only the well-off had the vote, such as that in England, were the norm in Europe. Not only were the pirates of the early 1700s a financial threat to trade, but a source of subversive ideas that could prove dangerous for governments, as theyy questioned the tyranny and oppression which dominated at the time. For this reason, pirates generally enjoyed the sympathies of the common folk, both in the Caribbean and Europe, so it was of the utmost important for governments and merchants to portray them as bloodthirsty villains and the enemies of humankind – Hostis humani generis. For the urban and rural poor, pirates championed the ideas of freedom and liberty in a society where slavery and servitude were widely accepted and rigourously enforced.

Surviving pirate articles

There are only a few remaining copies of pirate articles that have survived, as most pirate captains would have burnt them or thrown them overboard when capture was imminent in order to destroy evidence of their illegal activities. The seizing of the Articles by the authorities would almost surely lead to a conviction for piracy for all members in that crew, therefore it was imperative that they be destroyed to prevent them from being used against the pirates at their trial. However, not all pirates managed to dispose of their articles before capture, those of Bartholomew Roberts, Edward Low, John Phillips, and John Gow have all survived through Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Pyrates (1724) and The history and lives of all the most notorious pirates, and their crews (1725). While there is no surviving copy of Henry Morgan’s actual articles, Alexander Exquemelin describes ones which are likely to ressemble them in his book Buccaneers of America (1678).